Priests pulling no punches

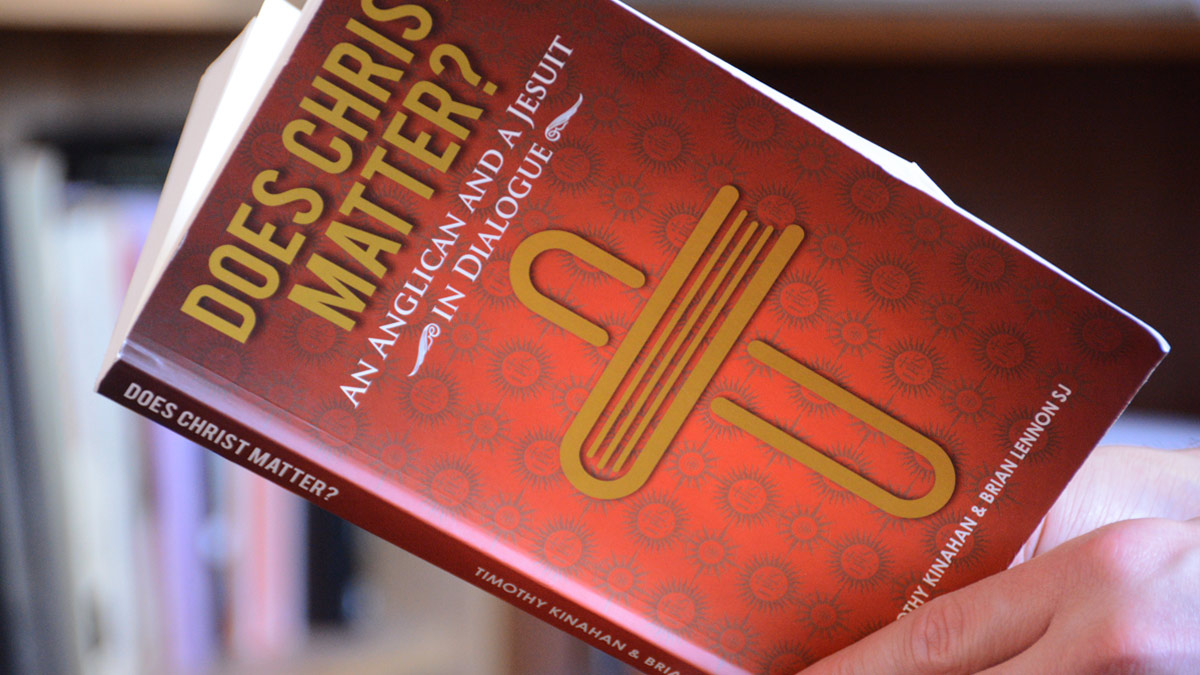

Brian Lennon SJ and Church of Ireland Rector Tim Kinahan, in their jointly-written book Does Christ Matter? A Dialogue Between and Anglican and a Jesuit, just published, argue that the IRA’s violent response to injustice in Northern Ireland was wrong. The failure to date to agree on an adequate response to what happened in Northern Ireland’s troubled past, they argue, has resulted in costly court cases, inquires and inquests. They also suggest that the first step toward an agreed approach would be a limited number of inquiries into collusion. In the light of the serious issues posed by Brexit, the authors express the opinion that Sinn Fein Westminster MPs should take up their seats there.

Presbyterian Minister Rev Tony Davidson launched the book on Thursday 23 November, in St Patrick’s Roman Catholic Cathedral in Armagh, at 8.00 p.m. It was also launched the following week in St John Baptist Church, Helen’s Bay, by Presbyterian minister Rev Denis Campbell.

The two authors reference the life of Christ throughout the book. They see him as someone who was immersed in the life of his people, compassionate toward, and challenging of, his followers. They cite the scandal it would have been for many upright Jews to see Jesus eating and drinking with tax collectors who collaborated with Romans and mercilessly taxed peasants who were on the border line of starvation. “He made friends with these tax collectors who were truly the enemies of the people. The parallel challenges for us today are obvious. If we want to be connected with Christ, if we claim to be Christian, what are doing to overcome our hatreds?”

Regarding the unjustifiable nature of the IRA campaign of the 70’s onwards the authors argue that it was wrong because it was politically self-destructive, with the IRA killing more people in the Nationalist community than the British security forces and Loyalists combined. They argue that the organisation could never achieve its aim of a United Ireland because its violent campaign inflicted untold suffering on thousands of people, and deepened divisions both within Northern Ireland and the island as a whole.

“Republican violence was particularly tragic because the political achievements of Nationalists in the 19th century had been achieved by constitutional means, not by violence,” they note.

The authors also focus on Loyalist violence directed mainly against the Catholic population in the North and sometimes those across the border. The response of Loyalists was also wrong they claim, saying that “There was not a shred of justification for the terrible killings and maiming’s they carried out.”

State violence is also addressed in the book where the authors reject what they claim is an over-emphasis on ‘innocent victims’. “Of course, there were thousands of innocent victims, but the phrase is too often used to pretend that the security forces never broke the law, which is simply untrue,” they say, adding, “Eighteen members of the UDR were convicted of murder, and eleven of manslaughter.”

They also note that the British Government failed to follow the norms of a Western democratic state. “Whilst many members of the security forces acted with incredible bravery,” they say, “report after report has shown the depth of collusion between the security forces and loyalist paramilitaries.”

This issue of collusion is one area where the authors feel tentative steps toward an agreed response to Northern Ireland’s troubled past might begin. “The people who benefit most from our failure to agree, are for the most part, lawyers in court,” they claim. “Inquires, court cases, and inquests are processes that seldom help those who have suffered move towards freedom.”

The authors discuss various approaches to the past and suggest that a small number of limited inquiries into collusion would help. “This at first sight may appear to be focussing only on wrongs committed by the security forces,” they say. “But in practice, such inquiries would likely expose further the extent to which the security forces had penetrated paramilitary groups. That might reduce the need for raising more questions about the past.”

The authors say that whether or not one took part in violence, no one can afford to be self-righteous. Self-righteousness, they say, “is one of the more stupid sins, an indicator that we do not know our own selves. So, while we should condemn the violence of the past we can never think of ourselves as morally superior to others.”

They also point out that Jesus was on a learning curve regarding diversity. They cite how he was challenged by a foreign woman, (Matttew 15) whose child he refused to heal at first because she was a foreigner. But in dialogue with her he learnt that it was not only his own Jewish people who were invited into his new community, it was everyone. “That raises questions for us about diversity in our churches, and our attitude to foreigners,” they conclude.

Brian and Tim first met before they were ordained when both were in the Ardoyne in Belfast in 1997. They served together on the Interchurch Group on Faith and Politics and the Community Relations Council, and were involved in back-channel discussions with paramilitaries during the 1990’s.

Timothy is an Anglican priest of the Church of Ireland and Rector of Helen’s Bay in the Diocese of Down and Dromore. Most of his ministry has been parish based within Northern Ireland, although he did spend 3 years teaching at Newton Theological College in Papua New Guinea. He has an M.A. from Cambridge University

Brian has been involved in community and ecumenical work for the past 40 years. He has written several books touching on the Northern Ireland conflict and was a founder member of Community Dialogue. He has led probably 1000 processes which have brought together ex-combatants and others, including those who have lost loved ones in the conflict. As well as this work he currently coordinates a group to support and encourage newly-released prisoners.

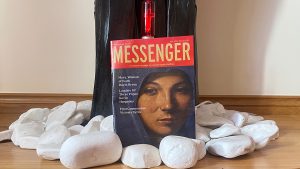

Does Christ Matter? A Dialogue Between an Anglican and a Jesuit is published by the Messenger Publications and can be purchased on line or you can contact the Irish Messenger office at 01 6767491: Email: [email protected]